Frank Frazetta: Hold and Release

By Dan Nadel

“Stop trying to paint like Frazetta! There’s only one Frazetta and he’s it!”

Burne Hogarth to his students

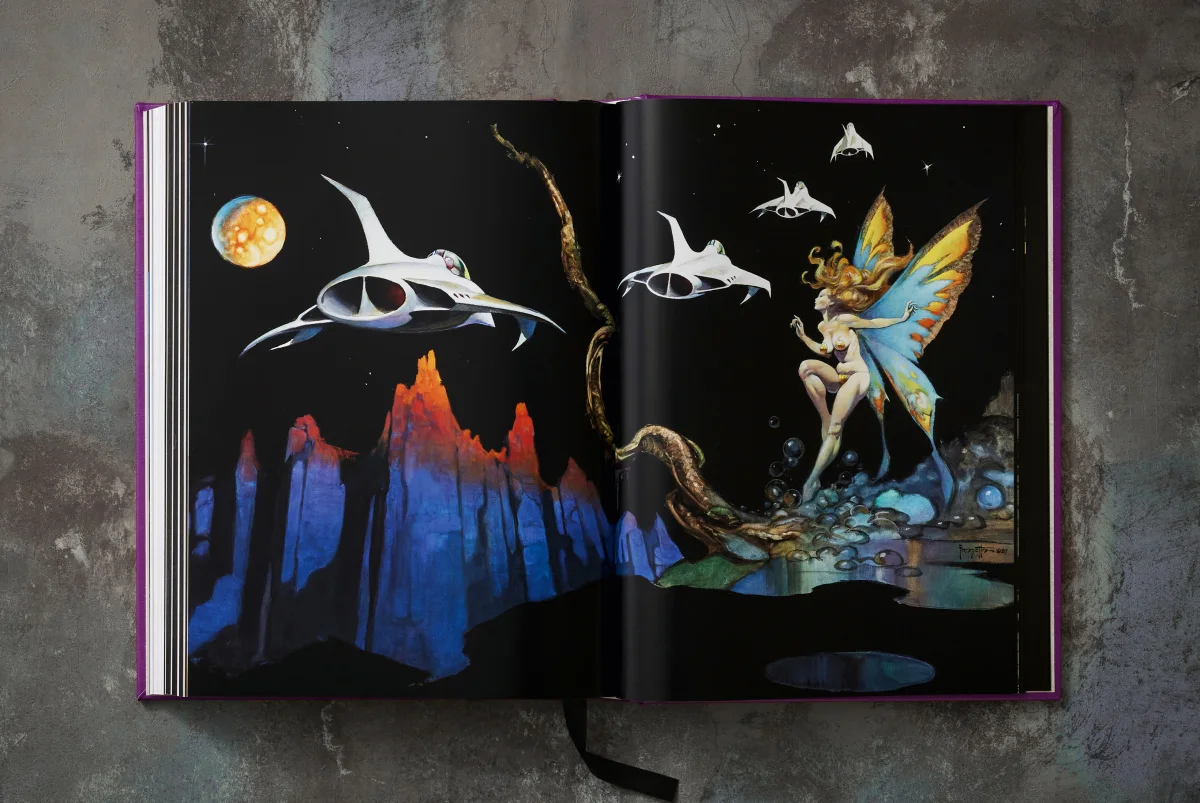

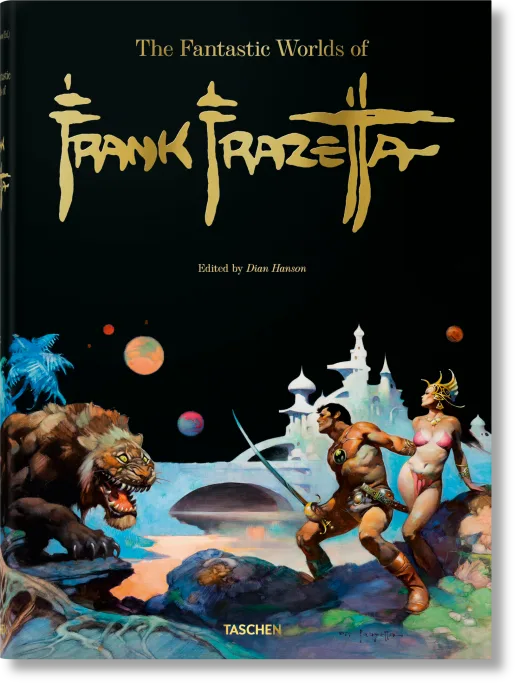

Image 1: Dark Kingdom, for the cover of Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane in Dark Crusade, sold for an astounding $6 million in 2023, setting records for the highest price ever paid for fantasy or comic art, let alone a Frazetta. The painting is best known as the album cover for Molly Hatchet’s Flirtin’ With Disaster, released in 1979. Oil on board, 1976.

Back in 1969, a few comic book and fantasy fans put together a maga-zine called Promethean. Psychedelic master Rick Griffin contributed a cover drawing, printed black on silver, of engorged eyeballs in mortal battle with a demonic Mickey Mouse stand-in. Above the carnage, instead of a logo, is the word “Frazetta” in Griffin’s near-unreadable Baroque lysergic script. The image is a perfect transmutation of the Frank Frazetta project: a centralized image of otherworldly brutal-ity composed in fluid darks and lights and rendered with precisely vigorous brushstrokes.

A Brooklyn-born hustler and brawler, Frazetta was not like his hero Hal Foster, a soft-spoken Canadian whose early-1930s Tarzan newspaper strip he called his “Encyclopedia Britannica.” In 1937, Foster began the decades-long comic strip story of Prince Valiant, a noble, upright, and righteous adventurer whose medieval world Foster rendered with stunning accuracy and vigorous life. Frazetta took Foster’s upstanding example, first urbanized it, and then blew it out into a landscape of forbidding darkness. If Foster was noble, then Frazetta was gloriously vulgar. But, like, say, Led Zeppelin, Frazetta was transcendently so. He didn’t imagine narrative scenes so much as emotional and psychological spaces not so dissimilar from the psychedelic mind space in which no rules apply. Drawings like his 1954 Weird-Science Fantasy cover or his 1967 painting for Conan the Conqueror are pictures of unbearably intense, nearly animated moments. His figures do it all in those instants—they’re lit purely for design purposes, bent, pulled, crossed precisely as he needs them, like the way a kid might abuse an action figure to get the pose he needs. This feel is enhanced by the eerie fact that Frazetta put his face on so many of his characters: conqueror, racist, sheriff, lothario. His face, his physical and mental states, are both text and subtext in his work.

Frazetta came by his coiled intensity honestly. He was born in 1928 and raised in a Catholic Sicilian family in a squat working-class home in Italian and Jewish Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn. Surrounded by a supportive and female-dominated family, he was a physical prodigy in drawing and athletics. Edgar Rice Burroughs was some of the first (and per the artist, only) reading Frazetta ever did. He remembered finding a stack of six or seven Tarzan books at age four—among them Tarzan of the Apes, Return of Tarzan, The Beasts of Tarzan—left in his cellar by an uncle who lived downstairs. Fascinated by the J. Allen St. John illustrations, he eventually read them all.

While attending grade school, young Frazetta began taking classes with Michele Falanga, an Italian neo-classical painter who was the sole proprietor of a single floor all-ages school called the Brooklyn Academy of Fine Arts just on the edge of Brooklyn Heights. Falanga taught drawing and painting rooted in the 19th century Roman neo-classical movement, emphasizing painting from life and humble subject matter. It was with Falanga that Frazetta learned brush control for subtle gradients, washes, and thin, taut lines. According to Frazetta, Falanga believed the boy was a prodigy, and planned to send him to Rome to further his education, but died just short of Frazetta’s 14th birthday, without having secured the travel plans. Frazetta never did make it to Italy, nor anywhere outside of the United States. For a couple years after, Frazetta and his classmates continued on their own, but it became “more like a club. I did life drawings and still lifes…we could go out in the field and paint some old church or whatever.”

Alongside classical drawing, Frazetta was absorbing the curves and spaces of Disney cartoons, including his favorite Fantasia, (the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence, designed by Baroque Surrealist Albert Hurter and art nouveau fantasist Kay Nielsen was an easily recognizable influence), E. C. Segar’s Popeye, with its incredible energy and violence, and Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates. In his boyhood drawings Frazetta was pulling and pushing Caniff’s slim patrician figures into stout forms and exaggerated poses. He was making people as he saw them in his neighborhood: dark-eyed, full figured men and women. Like a lot of other artistic children of immigrants in New York, Frazetta was drawn to comic books, then still a young indus-try populated mostly by artists who fell on either side of the draft: teenagers and middle-aged men. At 16 a family friend introduced him to the illustrator John Giunta, who was working for packager Bernard Bailey assembling comic books to sell to publishers. Giunta inked Frazetta’s pencils on the teenager’s character “Snowman.” Bailey placed it in Tally-Ho No. 1, December 1944, and at age 16 Frazetta was a published cartoonist.

From 1949 through 1953 he flourished as a cartoonist, producing comic book stories for Magazine Enterprises, National (now DC), and EC, including Shining Knight, Ghost Rider, and The Durango Kid. In 1951, he drew his own comic book for Magazine Enterprises called Thun’da, which he hoped might get him a shot at the Tarzan comic strip. Thun’da is a beautifully drawn jungle adventure story with plenty of panels swiped from Foster, and it did indeed make Frazetta’s name in comics.

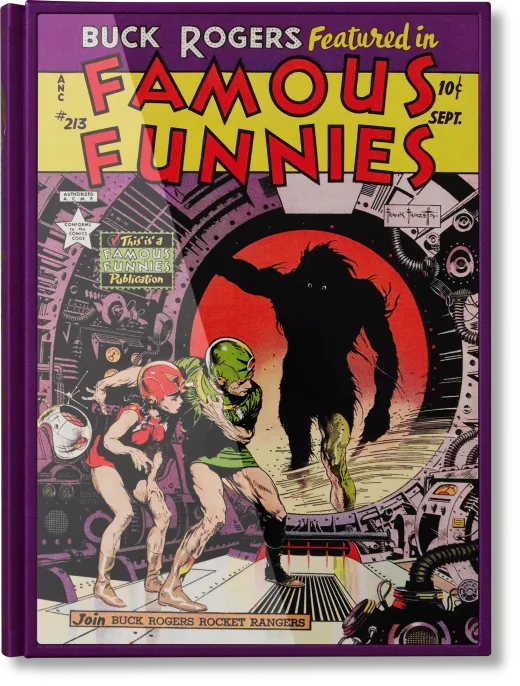

Working hard, for a guy who always claimed laziness, following Thun’da, Frazetta perfected his pen and ink drawings. First up was a year-long stint on a race car comic strip called Johnny Comet (known as Ace McCoy halfway through its run), which offered a chance to draw fast cars and beautiful women at impossible angles. During and after this run he produced eight Buck Rogers covers for Famous Funnies in 1954 and ’55 that shaped the look of drawn fantasy art for decades. Each drawing, like his best paintings, resembles a sudden inhalation and long held breath: a giant alights on a spaceship overwhelmed by Mars; a monster blows through a hull, only its eyes visible in the chaos; an octopus viciously ensnares a woman as Buck Rogers glides to her rescue; and in a drawing first rejected by Famous Funnies and ultimately published as EC’s Weird Science-Fantasy No. 29, a gnarled lone white man beats back dark brutes, bodies viciously splayed in every direction. These covers are drawn with not just evident relish, but the thing that is more difficult to pull off: real presence as both original drawings and printed objects. They radiate tension. Frazetta’s compositions of impossibly contorted bodies set the tone but his linework creates an atmosphere—knotted muscles, billowing smoke, and cascades of hair. Every component of these images flows so that there are no resting points for a viewer’s eye—the effect is vertiginous.

Frazetta never stuck with a title for very long. He’d make a splash, as with Thun’da, fall out with the art director or publisher, and move on. Some of it he would attribute to laziness: “Maybe [Hal] Foster didn’t like to play stickball and chase girls and goof off. I know that many artists are totally devoted…they’d rather work than eat or sleep. But my art was something that I ‘snuck in’ from time to time, between living. I never really thought in terms of just sitting there and devot-ing my life to it…never. I did it to tickle my fancy from time to time, usually if there was nothing else to do, or if it was raining.” Chasing girls was a consuming passion for Frazetta, who fetishized ankles, arms, necks, and liked a big round ass. In 1977, he recounted, “They told me 25 years ago, ‘You don’t put bras on your girls!’ Now, today’s women are Frazetta girls, long witchy hair, tits. My tits move, they sway. It’s all instinct. I didn’t know what I was doing. Crazy. Funny thing about my girls—I’m an ass man. Not a breast man. Oh, I love incredible breasts. But I like ass; that brings out the animal in me. They told me, ‘Frank, you paint all those hairs. You just don’t have to.’ They don’t know I separate the camel’s hairs on my brush and laid each hair and just swirl on the hair—ha! Lizards, now I’m not vain enough to think I can do better than nature. I echo nature, a smidgen of it, trees, leaves, a saurian jaw. People who think I invent all these things, they’re crazy. I like real women.”

In late 1953, he got a call from Al Capp to assist with drawing the hillbilly satire Li’l Abner, then among the most popular comic strips in the country. From 1954 to 1961 he penciled the Sunday pages and completed a handful of related assignments for the Capp studio. Capp’s strip was bawdy and fun work: ample, and amply proportioned women, slapstick action, and new settings for the restless artist. Frazetta was paid $150 a week for what he said was a day and a half’s work, leaving ample time for the aforementioned goofing around. Capp and his studio offered a good landing pad for Frazetta—steady work as a cartoonist was not easy, and he was able to put down roots—he married Eleanor Kelly in 1956 and soon began a family.

But as the 1960s began, Capp’s popularity, and payroll, were in decline, so Frazetta struck out on his own again in 1961. He picked up work drawing illustrations for men’s magazines Gent and Dude, and a handful of romance paperbacks, but he had a bit of trouble getting mainstream illustration work. He was still working in his classic style, which a decade later was beloved by fans, but disdained by art directors in thrall to the refined expressionism of Bob Peak or the classed-up deco of Milton Glaser. Fortunately, running alongside the beginning of cultural change in the 1960s was a boom in pop culture nostalgia, as the early generations of comic book, sci-fi, and fantasy fans grew into adulthood and began publishing ventures of their own. Comics strips started getting the reprint treatment and pulp writers and magazines were suddenly coming back in vogue—it helped that pulps offered cut-rate, or even free material for reprinting in cheap paperbacks sold in drugstores across the country, the more eye-catching the covers, the bigger the sales. It was in this old/new world that Frazetta, a virtuosic, wild traditionalist, found his footing.

His old friend Krenkel (“He helped convince me that I could do great things. I didn’t really need convincing, but he twisted my arm and pushed me a little. He called me a timewaster and a goof-off, and made me feel guilty about it.”), was contracted for Edgar Rice Burroughs’s cover illustrations by Ace Books, a dominant paperback publisher in those years. Unable to keep up with the demand, Krenkel put Frazetta forward, and his first cover, Tarzan and the Lost Empire, appeared in 1962, leading to many more. Thanks to another Fleagle turned Mad staffer, Nick Meglin, his grotesquely funny portrait of Ringo Starr graced the October 1964 back cover of the magazine. It rang a cultural bell like Basil Wolverton’s “Beautiful Girl of the Month” cover for Mad a decade before, and suddenly Frazetta was in demand again. Movie poster requests came in, first for Woody Allen’s What’s New Pussycat?, and then many others wanting crowded slipstick scenes à la Al Capp and Jack Davis.

Then, tapping into his old fans, Frazetta began working for James Warren’s EC-inspired comic magazines Creepy, Blazing Combat, Eerie, and Vampirella. He painted what he pleased for those covers, develop-ing what became his mature style. His designs are as clear as 1930s advertising: single focus, deep spaces, and color ways that move the eye through the image without ever straying from the center. He was undistracted by fidelity to gravity, let alone costumes or narrative. Only the feel of the picture itself had to work. The quick brush strokes he used as shorthand shrunk to barely visible splashes of color, and the whole image was given additional punch by the absorbent paper stock. In a moment of pop gloss, Frazetta offered a hyper-sexualized, often forbidding fantasy world—energetic, immersive, private. This mode would reach a peak when he left Ace (he felt disrespected) for a smaller outfit called Lancer, run by a couple of refugees from the old-time comic book and pulp magazine world. At Lancer he launched the company’s reprint editions of pulp journeyman Robert E. Howard’s 1930s tales of Conan, a wandering warrior of little moral character but a voracious lust for life. “Conan came to me at exactly the right time …” he remembered. “I had something to prove…the pay was in a different ballpark, and they treated me fairly and with respect. I was ready to do much better work, which I did.”

And the rest is fantasy art history.

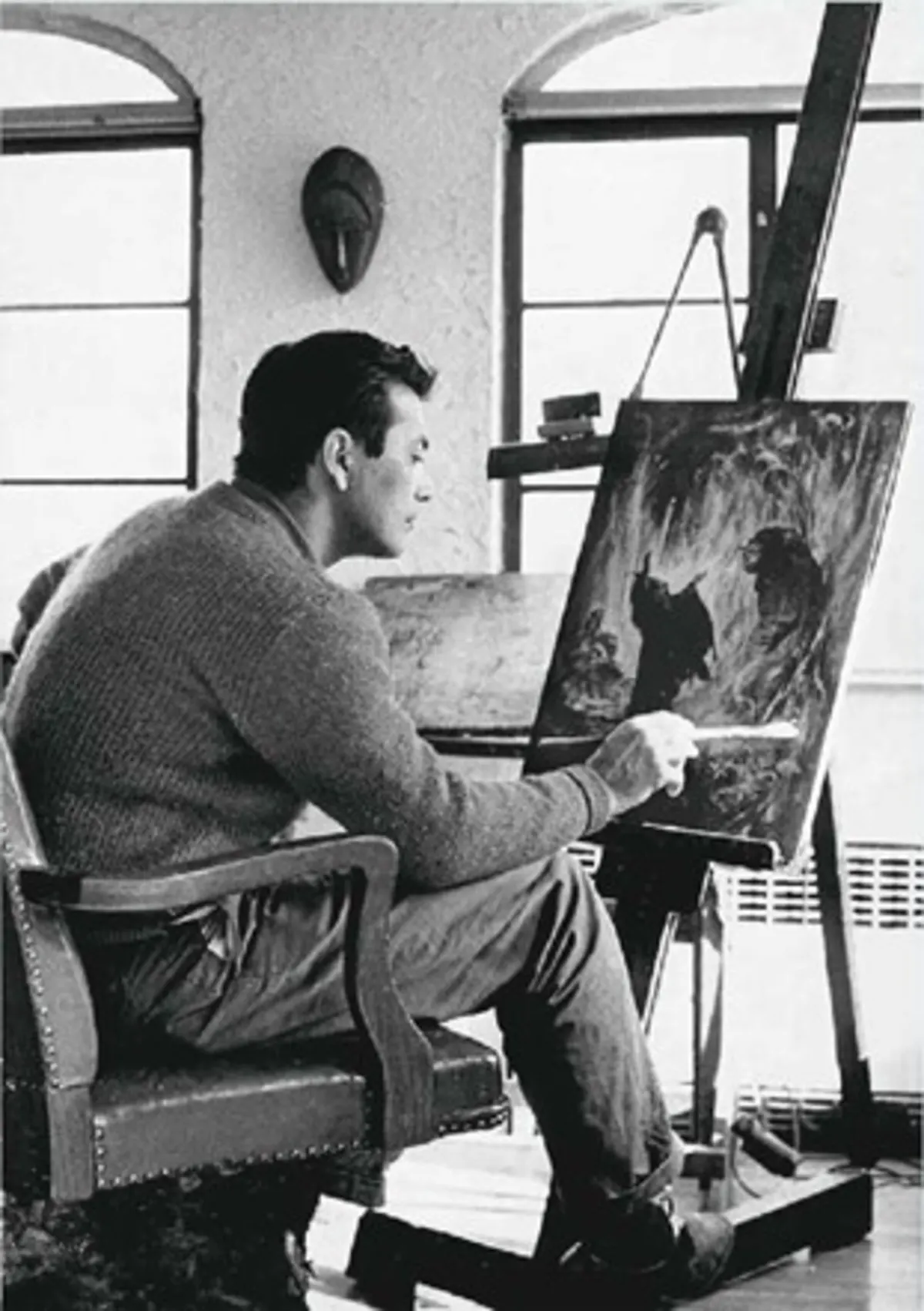

Frank Frazetta in his Brooklyn studio, 1966.

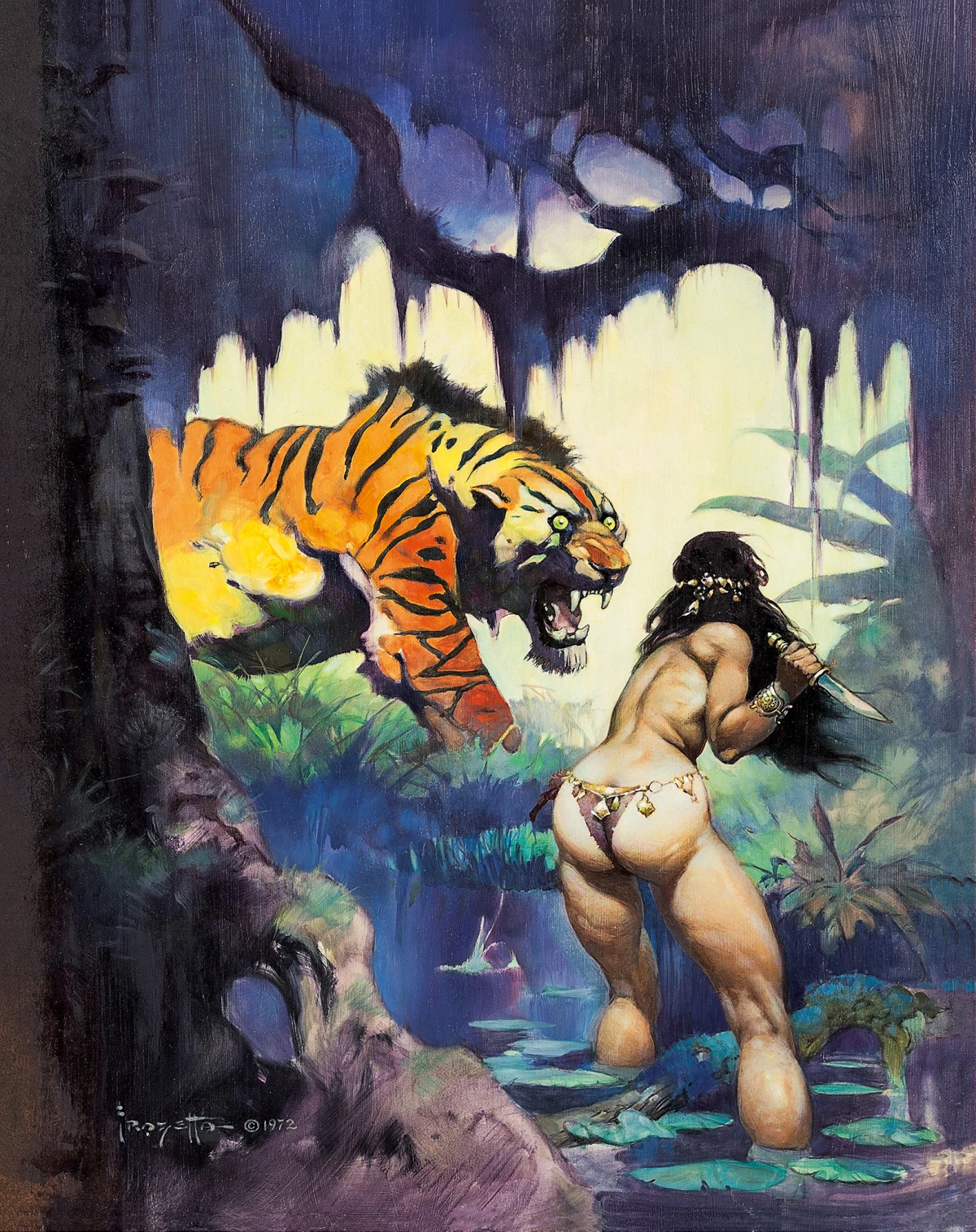

Nobody did female flesh like Frank Frazetta, and no booty was better than Princess Duare’s for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Escape on Venus. This painting, understandably, was used on several reprints of the novel.

Oil on board, 1972. Courtesy of Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc.